Prof. Peter Warr, Ph.D.

Australian National University

Summary of keynote highlights by

Assoc.Prof. Amornrat Apinunmahaku, Ph.D.

Prof. Peter Warr from the Australian National University explores the sources of economic growth by examining the theories of prominent economists like Robert Solow and Paul Krugman. He relates these concepts to Thailand’s economic landscape, using data to highlight how various factors have influenced the country’s growth trajectory and what this reveals about economic development more broadly.

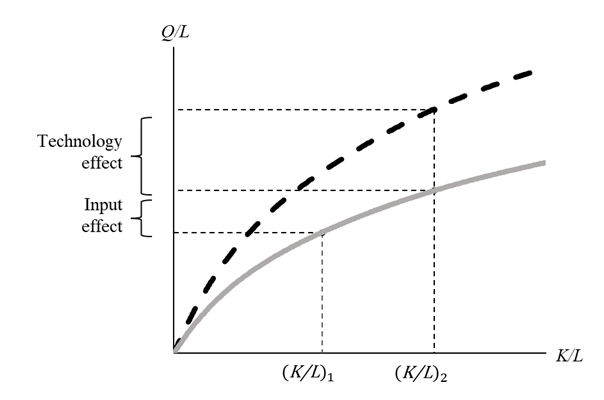

Prof. Perter Warr mentioned that in 1957 Robert Solow invented the subject of growth accounting: the decomposition of growth of output per worker into a component due to increasing the quantity of inputs and a component due to increasing the amount of output per unit of those inputs. Figure 1 makes this distinction clear.

Figure 1. The Solow model of growth accounting

The solid grey line shows the production function in period 1. This is the amount of output per worker produced for each level of the capital stock per worker. It shows diminishing returns: for each additional increase in the capital stock per worker the additional amount of output per worker declines. If the capital stock per worker increases over time from (K/L)1 to (K/L)2 the additional amount of output per worker that is obtained is shown on the vertical axis. This is the input effect. Now suppose that over the same period the production function shifts to the dashed black line. The same increase in the capital stock per worker causes an additional increase in output per worker that Solow said was due to technological change. Solow used data for the United States to argue that the input effect accounted for only 12.5 per cent of output growth per worker and technological change (measured as a residual) accounted for the remaining 87.5 per cent.

In a very famous 1994 article in Foreign Affairs called “The Myth of Asia’s Miracle”, Paul Krugman applied these ideas to Asia. He argued that for Asian countries input growth accounted for all of Asia’s rapid growth being experienced at that time and “technological change” explained almost none of it. He also said that Asia’s growth was unsustainable because if all the growth is due to adding to the capital stock diminishing returns means that the growth has to slow down.

There were two problems with Krugman’s argument. First, his argument (like Solow’s) is based upon a one-sector framework. Second, Krugman drew upon growth accounting studies conducted by other scholars for his evidence, as his article makes clear. But these studies were mainly based on data from Singapore and Hong Kong. These two city states differ from nearly all of the rest of Asia. They lack low-productivity traditional agriculture. They import nearly all their food. Does this matter?

It was argued that the movement of people out of low-productivity agriculture to higher productivity industry and services is a major source of Asian growth that Krugman overlooked as his evidence was based on economies that are not typical of Asia: Singapore and Hong Kong. They have no agriculture.

Extending Krugman’s framework, to understand productivity growth we need to distinguish three sources, not just two:

- growth of factor inputs (labor, physical capital and human capital) relative to population;

- growth of the productivity of these factors, through technical change; and

- growth of aggregate output per worker due to the reallocation of labour from lower-productivity sectors (mainly agriculture) to higher-productivity sectors (mainly industry and some services).

Krugman focused on (a) and (b). These are within-sector sources of productivity growth. He missed (c), which is a between-sector source of productivity growth.

In terms of Thailand, using data from the Thai government’s National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC). Thailand is far more typical of Asia than Singapore or Hong Kong. Like most of Asia, Thailand has a large agricultural sector.

But average productivity (output per worker) is low in that sector.

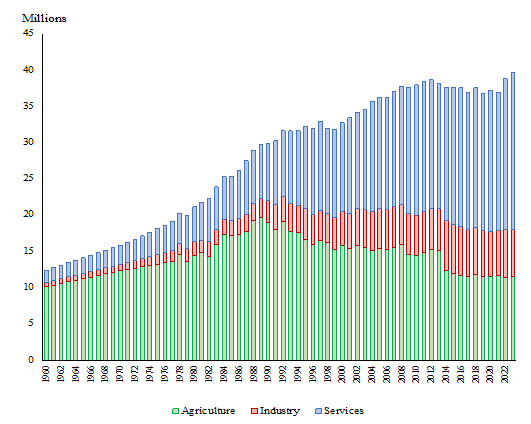

Figure 2 summarizes the changing sectoral composition of employment in Thailand from 1960 to 2023. As a share of total employment, employment in agriculture has declined throughout this long period. The absolute number of workers employed in agriculture has declined since about 1989. About two thirds of these workers leaving agriculture have gone into the services sector and about one third into industry.

Figure 3 now combines these data on employment with data on the composition of GDP in Thailand over the same period. GDP is the sum of value-added in each sector. The data show that value-added per worker in agriculture in agriculture is much lower than in services or industry. The movement of labor out of low-productivity agriculture into higher-productivity services and industry is a source of output growth that Krugman overlooked. How important is it?

Figure 2. Employment in Thailand, 1960 to 2023

Figure 3. Productivity per worker in Thailand, 1960 to 2023

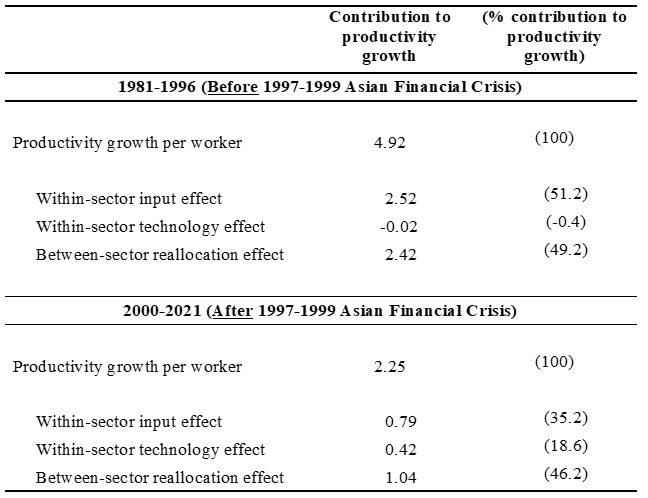

Table 1 now summarizes the application of the three-component decomposition described above to the data for Thailand, using the above data and other data on productivity growth published by the NESDC.

Table 1. Sources of aggregate productivity growth per worker per year, 1981 to 2021

These estimates confirm that the 1997-99 Asian Financial Crisis was a turning point for Thailand. Since the crisis, annual productivity growth has been less than half of that before the crisis. The decomposition helps in understanding the reason for that. The largest change is the decline in the within-sector input effect. This consists mainly of a decline in the rate of growth of the physical capital stock per worker. Investment in physical capital has three components: private business investment; public investment; and foreign direct investment. The first is by far the largest and the decline in this component is the main reason for the large drop in the within-sector input effect.

The results also show that the between-sector reallocation effect has been important in both periods, explaining almost half of the productivity growth per worker in both periods. This contributor to productivity growth also declined, but it was not as important as the input effect.

To raise long-term productivity growth significantly, an increase in the level of private sector investment will be required. The policy measures that might achieve that therefore deserve close attention.

Read news about NIDA International Conference 2024